Coronado’s Castle

By Joshua Dana, CHS Senior & Former CHA Intern

Coronado has a storied history in connection with the film industry going all the way back to 1897, but nothing compares to the brief period from 1915 to 1916 when Coronado was the center of it all. Siegmund “Pop” Lubin, the head of a Philadelphia-based global silent movie empire, was looking for a location for a new studio to expand the western division of his company and turned to Coronado.

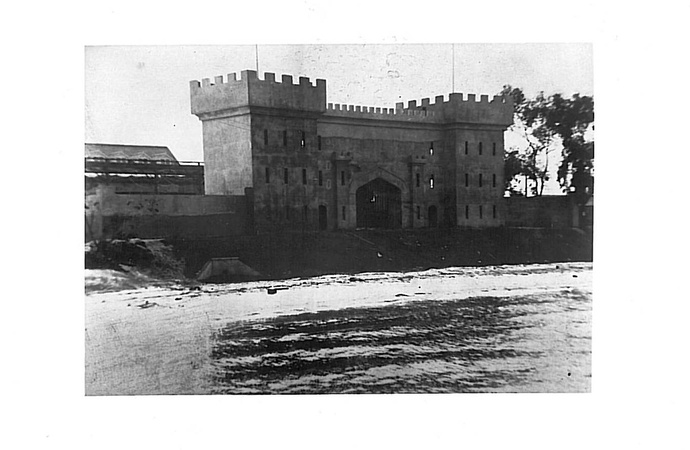

At the corner of First and Orange, today the site of a large condo complex across the street from Nicky Rottens, he constructed a massive studio with an English-style castle wall and a large gate facing the bay to keep away prying spectators. It’s beaches, the Hotel Del Coronado, the polo field, the ferries, and the many cottages dotting the island offered ideal exterior locations to break up interiors which were, in those days, filmed entirely in three-walled sets. After a lavish opening ceremony featuring guests such as former President Taft and (then Colonel) Pendelton, the company was set on a rigorous production schedule, shooting on average six short films a month. The cast and crew were made up of a colorful collection of characters, all led by Wilbert Melville. Melville, commonly referred to as “the Captain”, was credited as the executive producer of every production. In addition, he drew from his military experience in writing several scripts for military dramas along with local retired Capt. Reifenberick. Another notable writer employed at the studio was Josephine McLaughlin. She worked her way up from being Melville’s stenographer to the head of the scenario department in the studio’s closing months, a rare transition for women working in the film industry during that period. In terms of directors, the studio had two main leaders: Melvin Mayo and Edward Sloman. Of the two, Sloman would have the longest career, working for several more decades on projects with prominent stars.

The directors and writers often wove their personal interests into the films they created, which were all dramas. Such topics included the Secret Service in Meg o’ the Cliffs, criminal justice reform in The Convict King, and several prominent films like Vengeance of the Oppressed and The Embodied Thought highlighted the discrimination of Jews. Lubin himself was Jewish, and many of the people he employed were as well, making them acutely sensitive to the issue. Despite their experiences, however, Lubin allowed his directors to make incredibly racist films. This was a sadly common reality in those days.

Life at the studio was rough, with Melville being notoriously hard to work for. Many cast members frequently came and went. The directors faced a particularly grueling schedule because he had them direct, act in, and edit their own films! By the time the studio closed, both directors and several of the main cast members had quit.

The saddest fact in the story of Coronado’s film legacy is that the vast majority of the movies made here are lost forever. The highly volatile and flammable nitrate film stock used from almost the beginning of cinema until the late fifties whose sparkling layer of silver gave the theaters that showed them the moniker of “the silver screen” also contributed to the wiping out of a generation of art. Chemical decomposition along with the fact that distributors did not see the need to keep them has meant that up to 95% of American silent films are lost. Of the more than fifty films made in Coronado by Lubin, only one survives completely intact. It is housed as an unpreserved original nitrate print at the vaults of Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision in New Zealand. They were kind enough to examine the film for CHA for free and send a selection of still photos from the short. In Meg o’ the Cliffs, 546 Palm Ave. (still standing) can be seen, and in another scene, local gardener and French immigrant Alphonse Pierrot was, like many locals, an extra. He would sell potted plants which can be seen in the background. Thanks to the generous donations of several locals, CHA is now working with Ngā Taonga to obtain a digital copy to show in Coronado. None of these films have been seen here in more than a century.

Read a notice from October 9, 1915, about the "New Lubin Studios in Coronado"! Click on the link below.

https://archive.org/details/motography00test/page/728/mode/2up/search/coronado