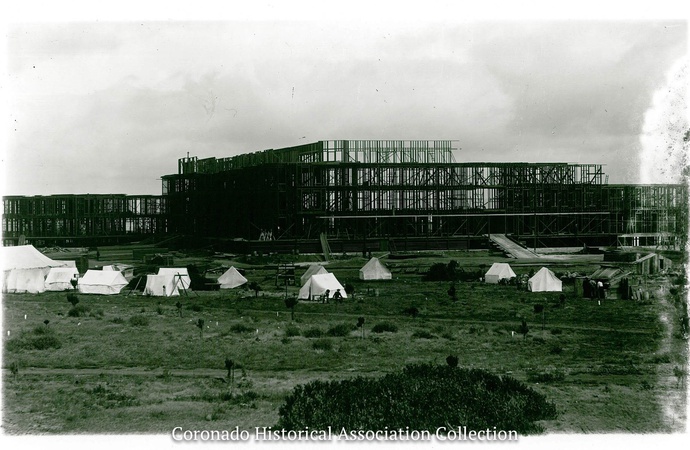

The all-wood Hotel del Coronado was built in one year, 1887, with a considerable number of Chinese immigrant laborers, brought south from San Francisco and Oakland. Their pay was reputedly around $2 a day.

The use of immigrant Chinese laborers in the West in the late 19th century produced massive infrastructure efforts like the Transcontinental Railway and the California Southern Railroad, which went from San Diego to Oceanside, then northeast to Barstow. This railroad’s construction ran from 1880 to 1885, bringing Chinese laborers from northern California as a non-union workforce. The laborers were vilified but hired when it seemed that white laborers would not work for the payment of $2 a day, an exploitative approach with a long history. The Chinese were described as “unskilled,” which may have been a justification for their low pay and some way of assuaging the pride of the unemployed white workers. Either way, these Chinese men experienced a large part of anti-immigrant bigotry in the West well into the 20th century.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 outlawed any future entry by Chinese people into the United States. In 1880 the Chinese population in the U.S. (mostly on the West Coast) was 105,465 (possibly an imprecise figure, given the difficulty of counting people who may not have wanted to be counted). The 1880 census shows the population of the entire country was 50,189,209 and that of California 864,694, thus the Chinese percentage of the population in 1880 was 0.021 and 12.14, respectively. The act was both protectionist and racist in intent: the foreigner was blamed for low wages and economic uncertainty. It was a helpful way of deflecting the vagaries of an unregulated economy onto forces with little to no power of their own.

Another significant building project in Southern California in the late 1880s was the elegant grande dame of Coronado, the Hotel del Coronado. Here, too, Chinese workers were brought in from the north to help build the eminent hotel in just one year. There was much talk in the press discouraging the hiring Chinese labor but to no avail, as they were certainly cheap and expedient labor, as proved by their work on railroads. In a Coronado Evening Mercury memorandum, Elisha Babcock, Jr., laid out his company’s policy on their construction employees: … We never use Chinese labor when we can get white labor to do the work, and all the talk on this subject has been for political effect… (12 November 1887). Despite this, the accepted history is that there were several hundred Chinese workers who contributed to The Del’s creation. Indeed, barracks were built to house them close to the building site. An article in the same newspaper on 28 June 1887 laid bare the issue of Chinese labor thus: … One of the largest corporations in California—the Coronado Beach Company—has always had to employ numbers of Chinamen from the fact that the amount of work to be performed could not be done any other way. The fault is attributed to…scores of white men…who prefer to tramp, beg and steal rather than earn two dollars per day at some honest work; four dollars a day would be no more inducement to them than half that amount. The author also cites smaller-scale businesses—laundry and vegetable sellers—that were run by Chinese immigrants and patronized by white customers because of the cheaper prices, who also found time to denigrate those services and products as “filthy.”

The effect of such articles is ultimately one of a sad jockeying for position among the varied inhabitants of the young town of Coronado Beach, a reflection of the larger state and national picture of the growth and development of a new country. There was much opportunity to prosper and little real reason to cast aspersions on those who were helping build that prosperity. We may therefore celebrate yet another aspect of the Hotel del Coronado—the unnamed Chinese laborers whose own fortitude contributed to her beauty and fortitude.